Having ‘Taste’ in the Age of AI

You have the tools to evaluate the quality of a thing

As I opened in my last post, I’m not wholly anti-AI. We need to continue figuring out where it fits in our work and personal goals as responsible designers, researchers, and product developers. If you're using it to augment your research, that's okay. If you're using it to prototype so you can get feedback faster, great! But hopefully, you aren’t using it to outsource your critical thinking or as a replacement for your informed decision-making. I especially hope that you’re also considering the ethical and environmental concerns around its use.

Anyhoo, a fascinating conversation has emerged in the AI discourse, particularly in relation to design. As far back as late last year, I started seeing opinion pieces about how taste will be more critical than ever as more products and services are developed using AI.

Daniel Bentes, an engineer and founder working in the AI space, put a great deal of thought last November in his article, "What AI Lacks and Might Never Overcome: Taste," After starting with a neuroscientific examination of taste, he added an incredible range of cultural and historical references from art, music, and dance. In the article’s opening paragraph, he said:

“While AI systems can analyze millions of artworks or musical compositions, they fundamentally lack the cultural context, emotional depth, and lived experience that inform human taste.”

Bentes’ article was ultimately not critical, as he concluded with many questions and ideas about developing AI systems that aim to combine human and machine capabilities, rather than just replicating human taste.

Martin O’Leary, a fintech growth marketer, posted “Why Taste Is The Only Moat AI Can't Copy in 2025” in r/entrepreneur a few months ago. There is a fairly balanced set of perspectives in the comments, but O’Leary ended it with this:

“The startups that will win aren’t the ones obsessed with what AI can do. They’re the ones obsessed with what only humans can. They’ll use AI as a tool, not a crutch, crafting products that feel like magic instead of just looking the part.

Here’s what happens when everyone has the same tools: mediocre taste makes you invisible. Good taste makes you unforgettable. And bad taste? That’s just infamous.

AI’s leveling the playing field. Good taste is what sets you apart.”

Sari Azout, founder of Sublime.app, wrote the following in her newsletter, “What matters in the age of AI is taste”:

“AI is powerful but taste-blind. It can make anything but it has no idea what's actually worth making.

But AI + your taste? That's the game-changer.

The more AI can execute, the more your eye for what's interesting – your ability to discern and curate what matters and why – becomes everything.”

Further in, she discussed the importance of a curated personal knowledge base to “teach AI to see through your eyes.”

Kira Klaas, a corporate marketing executive, recently shared the following in her newsletter, “When Everyone has AI, Only Taste Matters”:

“We shouldn’t be surprised. Every technological revolution follows a similar pattern: early hype, mass adoption, inevitable backlash, and finally, meaningful integration. We’re rapidly approaching the backlash phase with AI—and when it hits, the brands that have focused on taste rather than tech are the ones who are gonna make it through unscathed.”

It also wasn’t the first time that Klaas had written about taste. Last year, she wrote “What does Taste Mean at Work?”

Earlier this month, my former colleague and a design director at LinkedIn, Harrison Wheeler, posted a poll asking if people thought taste was a differentiator. He followed it up with, ”Do you have good taste? That’s debatable.” Harrison offered his perspective as a millennial:

“We've got to be careful about turning 'taste' into just another careless buzzword we throw around in meetings to sound like we know what we're doing because it carries some weight and it might come off as pretentious to people you’re trying to influence.”

He went on to write about how taste and intuition are linked, and that his “own gut feelings aren’t formed in isolation,” but “that doesn’t mean that he relies on intuition alone.”

(Be sure to subscribe to Harrison’s newsletter and podcast, Technically Speaking. We’ve had it listed on our recommended resources page since our book came out.)

Lastly, David Mendes, a brand design manager, wrote about the commoditization of taste in his newsletter. After sharing a few methods of how humans develop taste, and suggesting how they may not be dissimilar to how GenAI image models have been developed, he added:

“No matter how you look at it, from algorithmic to manual approaches, inspiration is becoming homogenized and taste flattened. An average of collective judgment. And that's not very differentiating.”

I know that was a lot, and there’s much more of this discussion out there. I recommend taking a moment to read any of the references above in full.

Although not specifically relating to AI, we wrote about taste in the final chapter of the Design Career Handbook. A few of the thoughts in the previous references align with our perspective. We know it’s not exactly the same, but we prefer to use a term that evokes less subjectivity, design sense. Here’s an excerpt:

Continue developing your eye and how you determine great design. Some people consider this taste, but we’re not fans of that term. When a person is said to have good taste, they are identified and associated with popular or desirable things—fashion, music, food, products, and just about anything. Sometimes, a person with good taste is a trendsetter. Things that they like become liked by others.

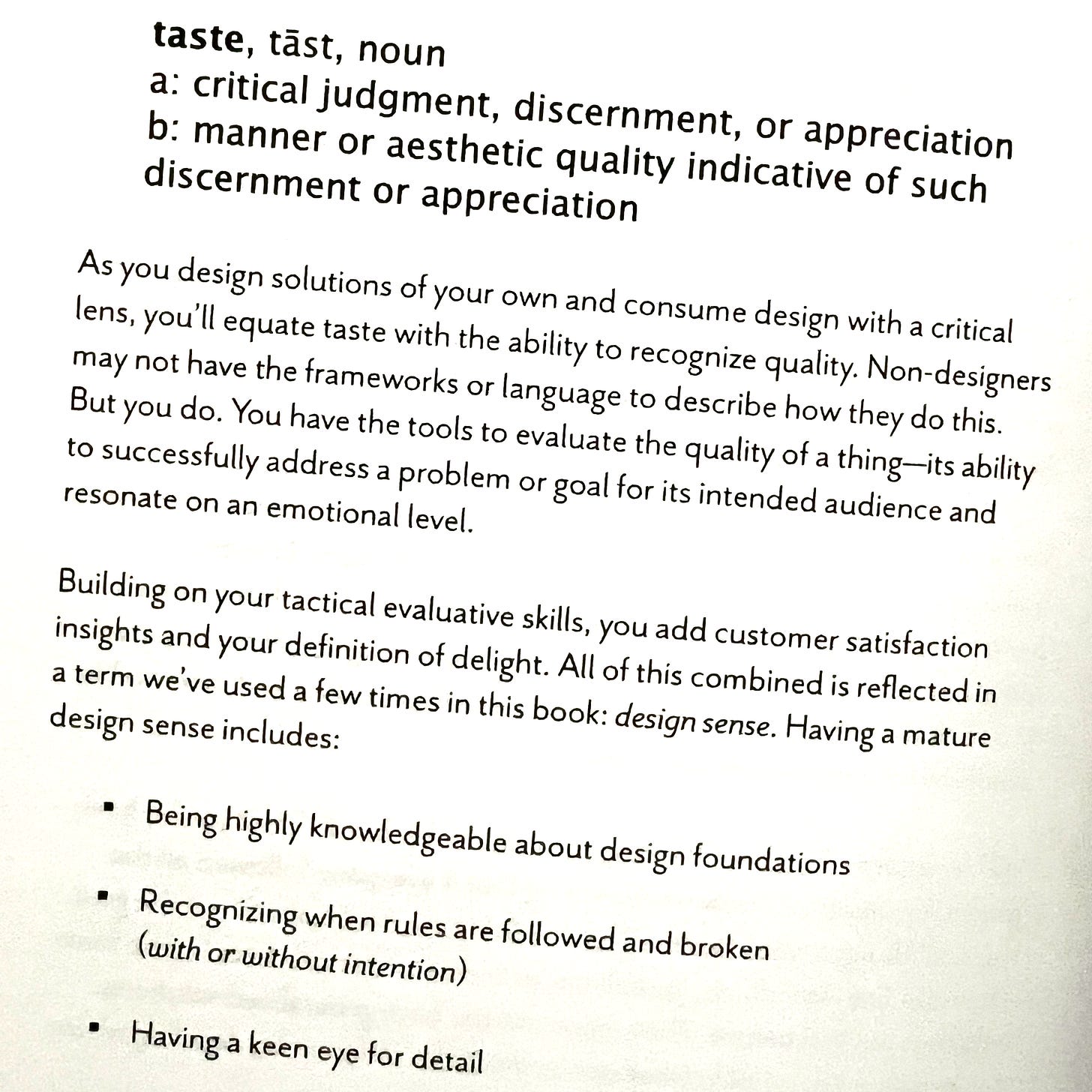

Taste is often considered a subjective and elusive trait; you have good taste, or you don’t. However, according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, the definition of taste is critical judgment and discernment of quality. As a designer, you’ve developed these skills for critiques—evaluating solutions based on principles, heuristics, research, and data.

As you design solutions of your own and consume design with a critical lens, you’ll equate taste with the ability to recognize quality. Non-designers may not have the frameworks or language to describe how they do this. But you do. You have the tools to evaluate the quality of a thing—its ability to successfully address a problem or goal for its intended audience and resonate on an emotional level.

Building on your tactical evaluative skills, you add customer satisfaction insights and your definition of delight. All of this combined is reflected in a term we’ve used a few times in this book: design sense. Having a mature design sense includes:

Being highly knowledgeable about design foundations

Recognizing when rules are followed and broken (with or without intention)

Having a keen eye for detail

Evaluating solutions thoughtfully

Making deliberate design decisions

Keeping in mind the why in your process

As you grow as a designer, all of this will become intuitive, and you’ll help others to do the same. From a practical standpoint, your interests will expand, and your ambitions will evolve as you form new perspectives through feedback and self-reflection on what you wish to accomplish.

Since last time:

It was truly special to give a talk on design career strategies in my hometown at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago! Check out the post for several highlighted topics and the t-shirt that I chickened out of wearing at the actual talk! 🖼️

We could always use your help spreading the word about our book. Please share with anyone interested in design. Besides everything related to job searching and portfolios, it also contains plenty of advice, tips, and stories for working designers looking to advance their careers.

If you already have it, thank you! We’d be grateful for your review on Amazon. ✏️

Don’t have it yet? The Design Career Handbook: Everything You Need to Know to Get a Job and Be Successful is available in paperback and ebook formats at Amazon and now also via Barnes & Noble online!